Iztok Ilc holds a BA in French language and literature and Japanese studies from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ljubljana. For the past decade he has been working as a freelance literary translator. He has translated works by Shusaku Endo, Kenzaburo Oe, Ryu Murakami, Haruki Murakami, Yukio Mishima, Rieko Matsuura, Kobo Abe, Yasmina Khadra, and the Marquis de Sade, among others.

1. What languages do you translate, and which takes up most of your time?

I translate from Japanese and French into Slovene. Translating from Japanese is without doubt more time consuming than from French.

2. How did you get your start as a literary translator?

When I was studying I always envisaged that I would work with literature. Translation somehow seemed to be the best option. The first window of opportunity opened in 2004 when Cankarjeva založba was looking for a fresh translation from Japanese as a part of the program ‘Japanese spring’ produced by the cultural center Cankarjev dom.

3. What is your process when you start a new project?

I don’t have a special process. Sometimes I don’t even read the book in advance, especially when the translation is commissioned. This is more common than people think.

4. What have been some of the most challenging projects? Why?

Challenges come in many forms, such as demanding stylistics, length or, ironically, even insipid content. But to give an example, translating Kenzaburo Oe was far from easy.

5. Which translations are you proudest of?

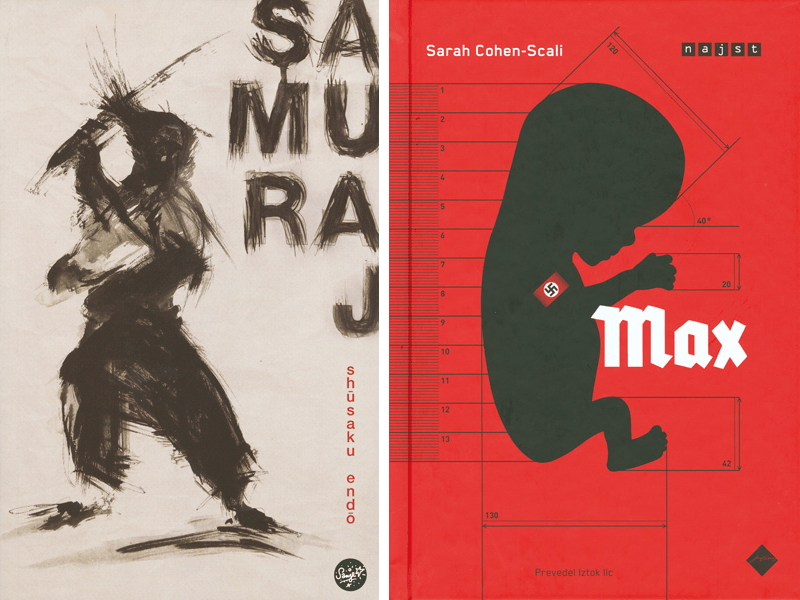

Endo’s Silence and Samurai, Murakami's Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Oe’s Nip the Buds Shoot the Kids and Sarah Cohen-Scali’s Max (from French).

6, What is your best-selling book?

I have no idea.

7. What is a book that you would like to translate?

Something easy and very well paid! But, facetiousness aside, I’d like to translate a good crime novel, a novel about music or maybe another ‘historical fresco’, as we like to say it in Slovene

8. Who are some authors whose works should be better known?

Definitely Shusaku Endo, Ryu (not Haruki) Murakami, Rampo Edogawa, and a whole series of women writers, such as Sawako Ariyoshi, Yuko Tsushima, Rieko Matsuura…Contemporary poetry and plays are also a big and unexplored land.

9. Do you ever have any contact with the authors?

Sometimes. Most of them are dead, anyway.

10. What are some misconceptions about your work?

There’s a lot of romanticizing around our work: how are we in dialogue with the author, how we are privileged to work with literature. But in reality there’s a lot of sitting, researching, checking, double checking, revising. That goes on for months and months. It can get very tedious. What the public doesn’t know is that we, literary translators, are a vast and deep repository of knowledge. We know a lot, we just don’t show it.

11. What is the market for translations like in Slovenia?

It is not as thriving as it was several years ago. Popular authors of course do sell, but an author which is popular abroad doesn’t necessarily have the same resonance here. Target audiences differ from country to country. There is complex array of different forms of government support for literature and authors (direct and indirect). In short: the Public Book Agency subsidizes literary translations and gives out several grants a year. The Agency also manages public lending rights, but all the money comes from the state. The Ministry for Culture takes care for social security contributions of those registered freelance literary translators who are entitled to get these paid by the state (not all of them are).

12. Why did you choose literary translation, as opposed to other forms?

I was naïve. Well, I saw a certain kind of intellectual prestige in it.

13. What advice would you give to a young person interested in this line of work?

If you are not into literature don’t even think about it. Then try first, pick a short story and do it. Start with something contemporary written in neutral language. Consult the translation with a mentor. Keep in mind that literary translation is not just looking for the right translation solution, but it also requires a lot of sitting and patience. Perhaps you’d better be an interpreter. And find a partner with a regular job.

14. How do you see the future of Slovenian translation?

There is no future. According to Janez Orešnik, professor of comparative Indo-European linguistics, Slovene has only 120 more years of life. I have the feeling that my generation is the last strong generation of literary translators. Literary translation into Slovene will slowly die out.