January 22, 2019

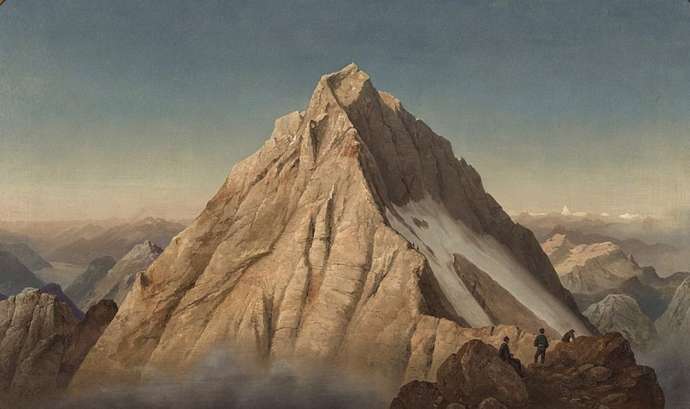

It is said that every true Slovene should climb to the top of Triglav, the highest Slovenian mountain, at least once in their lifetime.

However, recent reports of heavy traffic at the top of the mountain along with the trash trail that follows it are evidence that such an expression of national pride doesn’t come without the cost these days. Calls to drop the ‘everyone on Triglav’ idea and replace it with practices that are focused on preservation of nature rather than the defence of territory by repeated conquests of inhabitable lands have been becoming louder in the last two decades. Such a paradigm change is even more pressing since the struggle for independence ended with the final acquisition of the Slovenian statehood in 1991.

This article, however is not about what should be done about mass tourism at the top of Slovenia’s highest peak, but rather how it has all begun. How and why did Triglav and mountaineering in general become so tightly knitted into the fabric of the Slovenian national identity.

The start of an obsession

“To conquer the summit” is in fact a literal translation of a Slovenian expression for reaching the summit (osvojiti vrh), while the very idea of climbing to the top of a mountain instead of worshipping it from the bottom originates in the ideas of the Enlightenment.

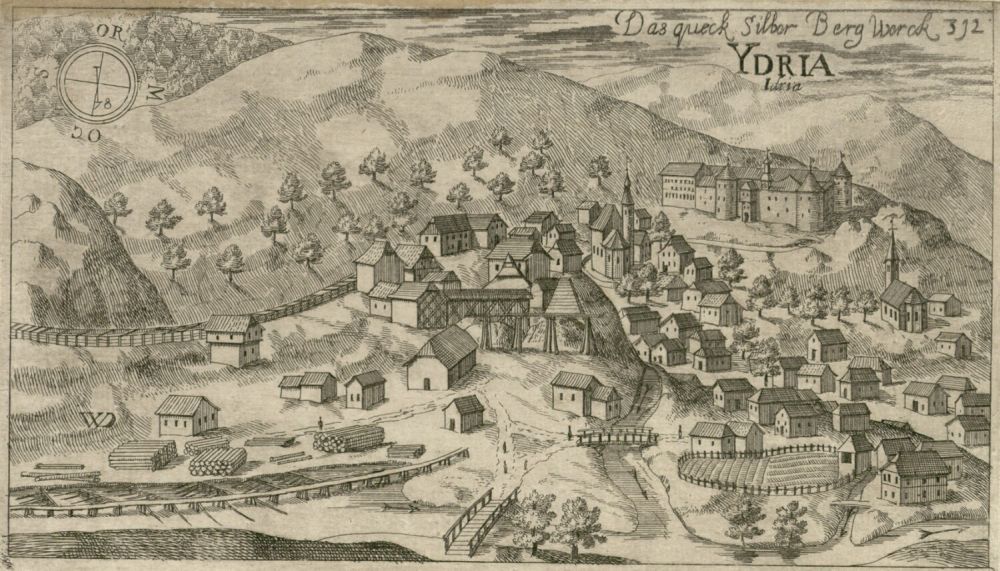

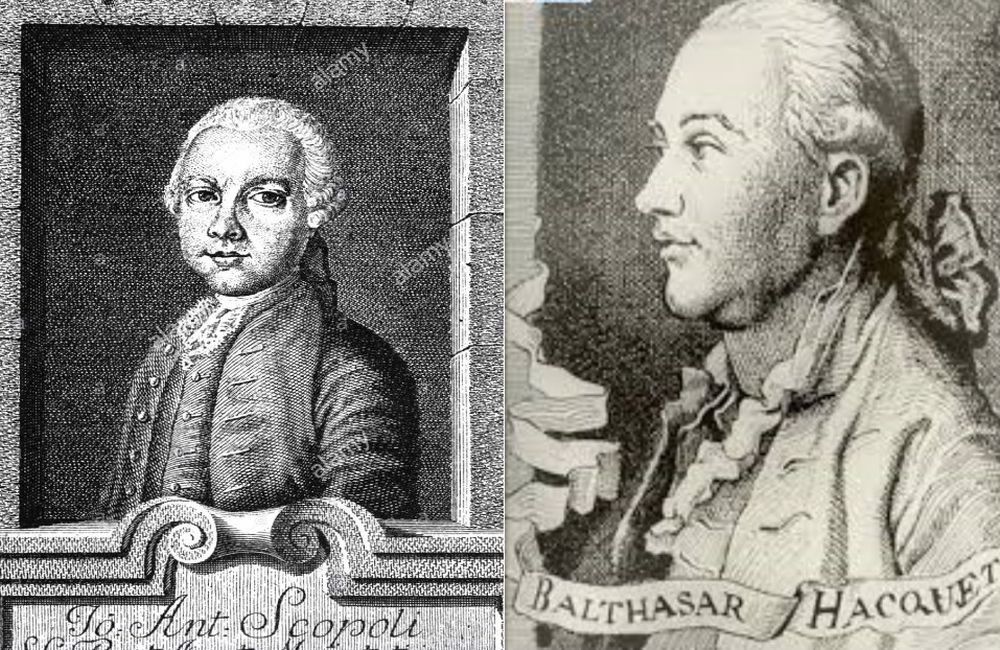

One of the most important places which allowed for the enlightenment to spread among the 18th century Slovenes was, perhaps surprising for some, a secluded mining town called Idrija, the location of the world’s second largest mercury mine. As such, Idrija attracted some of the Europe’s finest natural scientists of the time, in particular Giovanni Antonio Scopoli and Balthasar Hacquet. And both men played an important role in the series of events that lead to the first reaching of Triglav’s summit in 1778, which took place eight years before Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, was climbed.

Now, Triglav at the time was not Triglav today, equipped with ropes, iron fences and widened trails, and even though the peak lies below three thousand metres, it was quite a difficult mountain to climb, not something one could do on the first attempt. So how did the two enlightened thinkers influence the idea to get to the top?

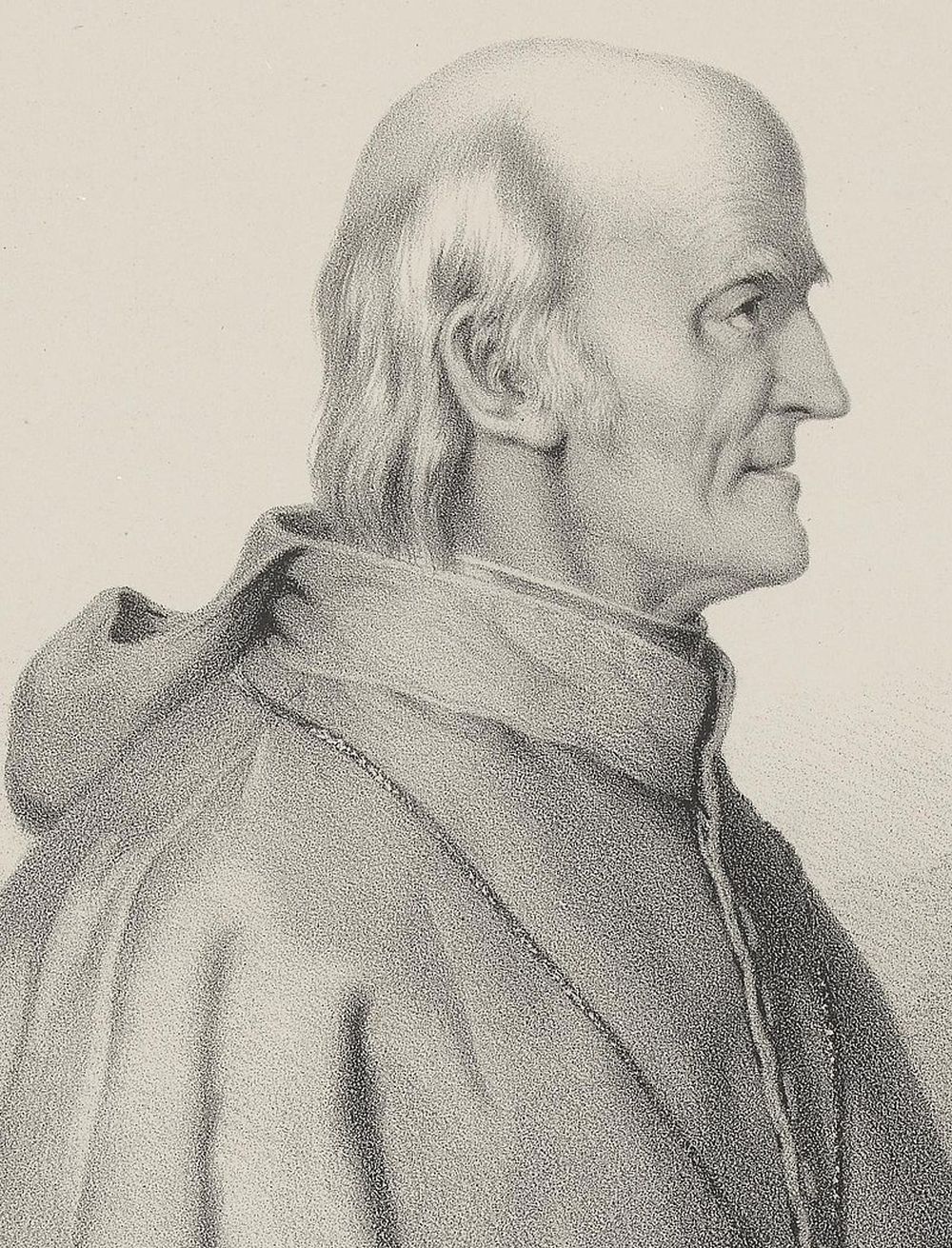

Scopoli, born in the Southern Tirol (today’s Italy) of the Hapsburg Empire, served in Idrija as the first mine physician between 1754 and 1769, a job which included extensive research on the surrounding botany (no antibiotics in those days), including the Julian Alps, the location of the Triglav massive. This is why Scopoli ended as the first man at the top of Storžič (2,132m) in 1758 and Grintavec (2,558m) in 1759. In 1760 Scopoli published a book on his findings called Flora Carniolica and kept a regular correspondence with no other but the father of contemporary taxonomy, Carl von Linné (aka Carl Linnaeus) in Sweden. The two communicated in Latin.

Apart from his inventory of over 1,100 plants from the Slovenian Northwest, Scopoli also founded an education programme in metallurgy and chemistry in Idrija, which he eventually left for professor’s position at several respectable universities in central Europe.

In Idrija, Scopoli was joined and then replaced by a French surgeon and natural scientist Balthasar Hacquet, who, intrigued by Scopoli’s work, came to Idrija in 1766. Hacquet, also credited with the first description of mercury poisoning symptoms, followed in Scopoli’s steps and attempted his first ascent to Triglav in 1777, but only reached one of the mountain’s lower peaks, Mali Triglav.

The natural sciences and Žiga Zois

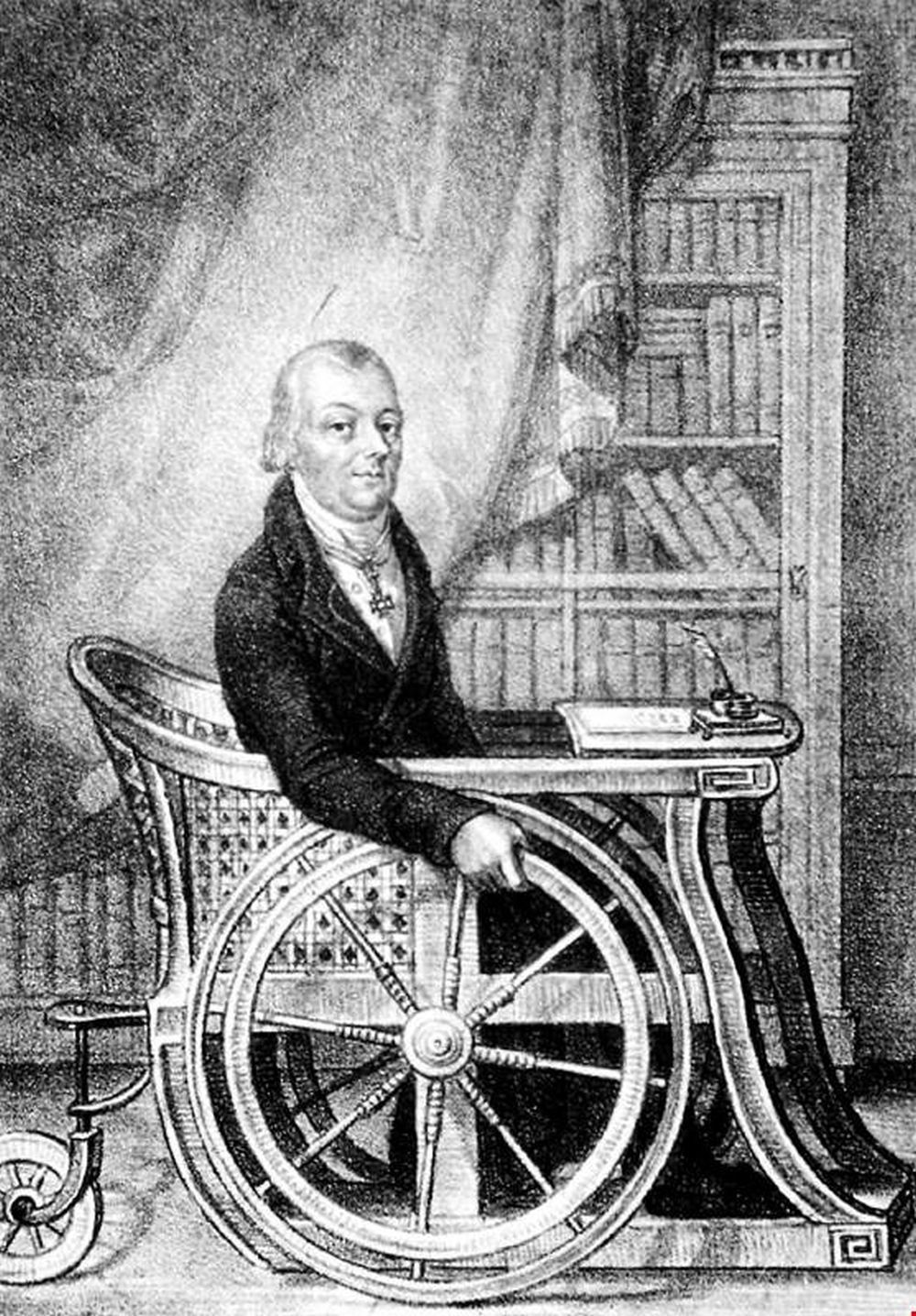

At the time Hacquet was also in correspondence with Žiga Zois (Sigmund Zois), a natural science enthusiast, geologist and at the time the richest Slovene, who had just purchased an ironworks facility (fužina) at the foot of the mountain in Bohinj.

Why Sigismund (Žiga) Zois decided to sponsor the first expedition to the top of Triglav in 1778 is not entirely clear, as the so-called Bohinj papers in which expedition details were discussed have been lost. According to one theory, the predominant reasons were to send someone on the lookout for possible new ore deposits. Another theory is that Zois got inspired by the failed attempt of his geologist pen-pal Hacquet. Either way, Žiga Zois presumably promised a financial award to anyone reaching the top and also organised an expedition, which eventually successfully reached the summit for the first time in 1778.

The expedition was led by Zois’ ironworks facility physician and Hacquet’s student Lawrence Willomitzer, who was to be accompanied by three local guides: Luka Korošec and Matevž Kos, both miners and a hunter Štefan Rožič. Although there is some debate about wether or not all of the men really reached the top, in 1978 the Mountaineering Association decided to depict all four men in a statue in Ribčev Laz, Bohinj, as “more first ascents are better than less”.

Vodnik makes it to the top of Slovenia

Besides researchers and the nobility (Žiga Zois was a baron), another group of people was interested in mountaineering in those early days: priests.

The first one to mention is Valentin Vodnik from Šiška (Ljubljana), who went to Triglav in 1795 in another of the expeditions financed by Zois. The main goal was to prove the neptunist theory on the sea origin of Julian rocks, and thereby refute the plutonist claims of the rock’s volcanic origin, a dispute Zois found himself in with an acquaintance from Transylvania, Johann Ehrenreich von Fichtel, whose claims on the upper parts of the mountain to be of volcanic origin were based on a simple assumption. To prove Fichtel wrong Zois needed a specimen from the top of the mountain that would show some sediment, which was eventually provided by Vodnik.

Valentin Vodnik, however, didn’t stay priest much longer after meeting Zois in 1792. He switched to teaching position at Ljubljana grammar school six years later. As such, both Vodnik and his patron Zois are part of the group responsible for the early experimentations with Slovenian nationalism, which in the case of Valentin Vodnik meant the use of what was then considered vulgar peasant language in poetry. Indeed, Vodnik’s 1794 ascent of Kredarica and then a year later of Triglav inspired one of his better poems, Vršac.

With Austria’s defeat by the Napoleon’s army, life changed significantly for Vodnik in 1809, when the newly established Illyrian province with its capital set in Ljubljana allowed him to teach in the Slovenian language. He became a principal of Ljubljana grammar school and a supervisor of vocational and handicraft schools. Vodnik marked this French move in support of local ethnic empowerment with an ode called “Illyria reborn” (published in 1811), for which he had to pay a price once the Austrians took their territory back in 1813 – he was banned from ever teaching again in 1815.

Alpinism evolves

In this circle of early priest alpinists we can also count the Dežman brothers, who also reached the top of Triglav in the years of 1808 and 1809. Among Slovenia’s most notable alpine climbers at the time, however, Valentin Stanič stands out as the first proper alpinist in a contemporary sense of the word. His ascents were often unique and daring, since he regularly climbed solo without a guide and even in winter time. He climbed various European mountains, including Grossglockner in 1800. In 1808 he and his guide Anton Kos reached the top of Triglav, where Stanič measured its altitude with a barometric device and only missed the exact figure by 7 metres, an admirable result for an amateur surveyor. Although it seems that his climbing initially served his scientific interests, Stanič later developed a much more sporting interest in trying to climb as many mountains as possible, to be the first one to reach unconquered summits, and on the way overcome hardships and experience happiness and excitement, attitudes that were very unusual and forward-thinking for the era he climbed in.

Despite this, most researchers, noblemen and priests would not head into dangerous mountain conditions without local guides, with this latter group less concerned with getting to the top of the mountain than they were with the opportunity to make some money for themselves and their families.

Enter the Slavs

In the middle of the 19th century several ideological attitudes developed in the mountaineering communities of Europe.

The sporty style of the British nobility on Europe’s most prominent mountains came into being with the help of local French and Swiss guides. This elitist style of climbing by a leisure class who could afford to travel abroad and mount expeditions was contrasted by the style of the Germans, who were climbing at home and thus needed less money to do so, and for whom mountaineering was less associated with class, prestige and conquest. Well, until the Slavs enter the picture.

For most of the Slavs, and especially the Slovenes, mountaineering was closely associated with a defence against language- and class-related Germanising influences, as seen, for example, in the use of new German names for mountains and other places that were originally in Slovenian, a process that increased with the growing number of well-organised German climbing groups who were visiting the Julian Alps at the time. On top of this, Napoleon’s short-lived Illyrian province, which planted the seed of nationalistic sentiment in the minds of the Slovenian masses, strengthened the assimilating pressures of the Austrian empire, which in turn generated much greater resistance. Mountaineering thus became part of the Slovenian national project, and Triglav as the highest peak in the Julian Alps was its symbol.

Read part two here