April 28, 2019

Money in Slovenia has existed in three different currencies since the country declared independence on June 26, 1991, the last one being the euro, introduced on January 1, 2007.

Before the euro, the Slovenian currency was the tolar.

And before the tolar, Slovenia used the Yugoslavian dinar.

The dinar was a troubled currency that went through several periods of hyperinflation, each one leading to a revaluation. From the mid-1980s on, the devaluation of money also started to affect the aesthetic value of the banknotes.

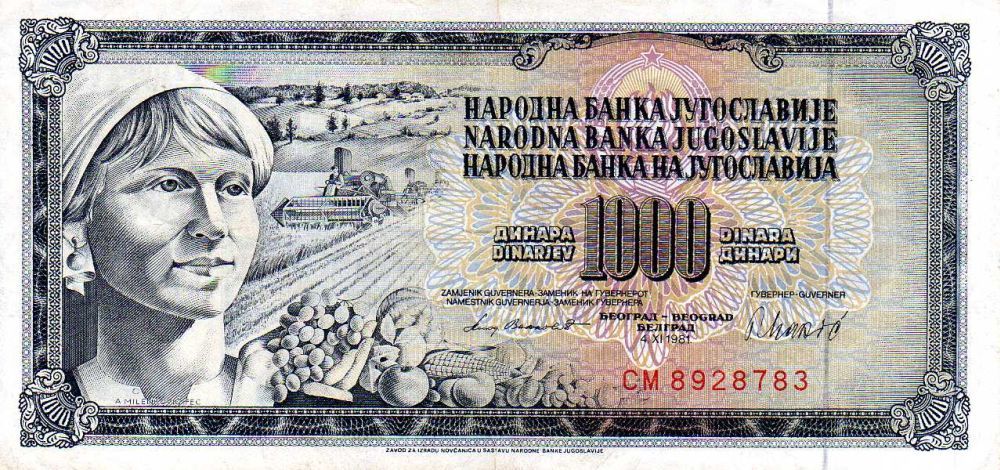

Shown below are the designs of banknotes following the first revaluation of the dinar in 1965, which were in use for about 20 years.

These banknotes were relatively detailed in design, depicted anonymous workers or statues and only changed slightly over time, mostly to update the font or background details depicting the nominal value. The 500 dinar note with Nikola Tesla was introduced in 1970 and another one, a 1,000 dinar bill, was introduced in 1974. This was also the last note designed in the old classic style of dinar, when it was still worth anything.

In about 1980 I was considered old enough to be given some change and sent downtown to buy my own ice cream. In a few years of this independent ice cream consumption, I started to observe a pattern; each new summer season the price of a scoop of ice-cream doubled. I found that quite handy as I could enter the new season prepared. Until one day the whole thing became unpredictable.

Changing money in Slovenia

That actually happened around 1985, when strange ugly money started to enter circulation. To encourage people’s trust into these notes, Tito’s face was put on the first one of them.

The Tito 5,000 dinar note was issued in 1985, the 20,000 bill in 1987, 50,000 in 1988, and the remaining four including the last one, the 2,000,000 dinar bill, all came out in 1989.

It seemed that money was devaluing faster than the central bank designers could draw.

The second revaluation took place on January 1st, 1990 with a new “convertible dinar” set at 10,000 : 1, basically cutting four zeros off, and from then on a whole devaluation spiral could continue.

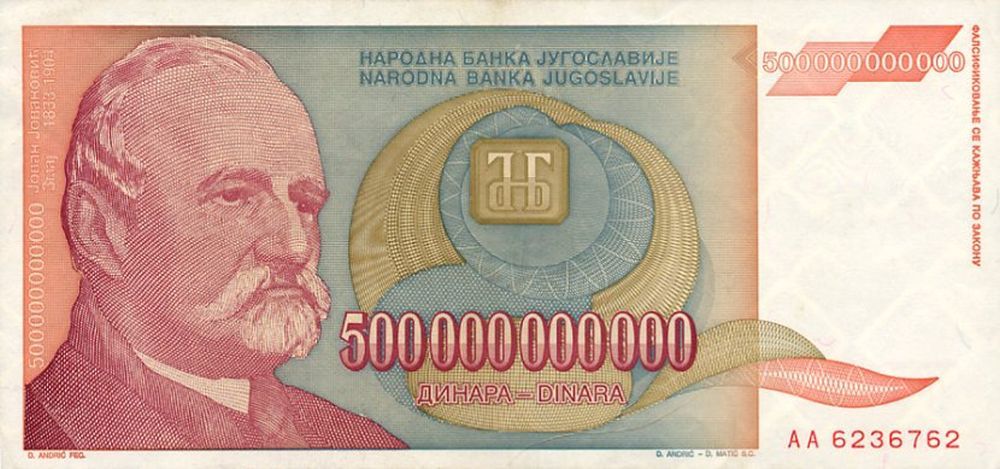

When the 5,000 bill was introduced in 1991, featuring the Yugoslavian Nobel Laureate for literature, Ivo Andrić, the country was coming to an end. This was the last dinar with writing in different languages inscribed on it, and the last one with the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia coat of arms.

Slovenian currency, a short-lived experiment

On October 8 1991 Slovenia switched to the tolar, on December 23 Croatia introduced the Croatian dinar, on April 26 1992 Macedonia adopted the Macedonian denar, and on July 1 1992 Bosnia and Hercegovina switched to the Bosnian dinar. This was also the date of the Yugoslavian dinar’s third revaluation and the beginning of a period of massive hyperinflation, which at its peak in January 1994 amounted to 313 million % monthly inflation, meaning that prices would double every two or three days.

Although Slobodan Milošević blamed this monetary fiasco on sanctions imposed on what was left of Yugoslavia by the United Nations in response to Bosnian War in 1992, earlier events suggest that this time of hyperinflation might have been mostly to his own destruction of economy in his attempt at securing power. As the Federal government’s Prime Minister Ante Marković figured out as early as on January 7th 1991, the Serbian parliament secretly ordered the Serbian National Bank to issue US$1.4 billion in credit to Milošević’s friends and political supporters. This illegal plundering of the state equaled more than half of all the new money the National Bank of Yugoslavia had planned to create in 1991.

The Yugoslavian hyperinflation of 1993/94 was at the time the second highest ever recorded, until Zimbabwe pushed it to third place in 2008. The absolute winner remains the Hungarian pengő in 1946. This peaked at 1.3 x 1016 percent per month (prices double every 15 hours), and when the forint replaced the pengő in 1946, the total value of all notes in circulation in Hungary amounted to 1/1000 of one American dollar.