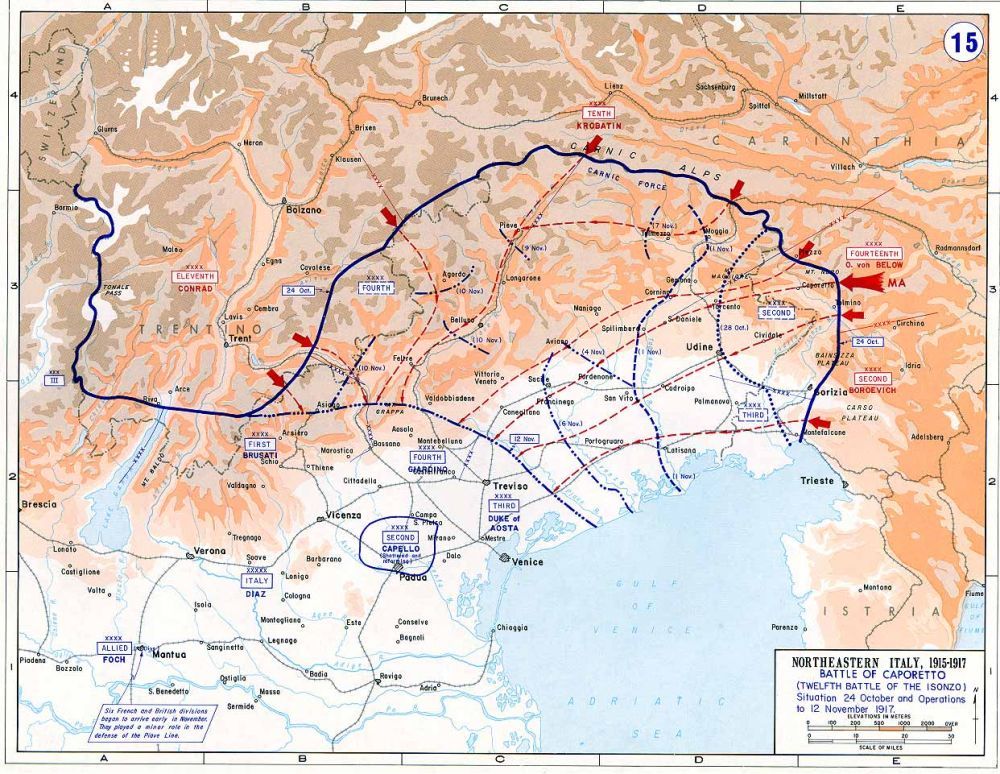

In 1917 on today’s date, the 12th and last Battle of Soča (Isonzo) started with the Austro-Hungarian forces being able to break into Italian frontline and forcing Italians to retreat about 100 km westward to the Piava River.

One of the Slovenia’s most scenic areas, the Soča (ITA: Isonzo) river valley, a filming location for fantasy movies like Narnia (Prince Caspian, 2008) and one of the main Slovenian tourist destinations, was also one of the bloodiest scenes of World War One. The last of these battles, the Battle of Kobarid (Caporetto), which started on today’s date, is also the one mentioned in Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms.

Italy entered WWI due to an alliance with Germany and Austro-Hungary that it had been part of since 1882. At the start of hostilities it refused to commit troops, claiming that the alliance was defensive in nature and that Austro-Hungary was the aggressor.

In 1915 Italy changed sides after the Triple Entente (France, Russia and Great Britain) promised it parts of the Austro-Hungarian territories, in particular the Southern Tyrol, Austrian littoral (today’s Slovenia), and Dalmatian coast (today’s Croatia) after a Austro-Hungarian defeat. In April 1915, Italy declared war on Austro-Hungary and fifteen months later it declared war on Germany.

Austro-Hungarian troops, in anticipation of the Italian offensive, moved from the border with Italy to the left bank of the Soča River to await the Italian army in a terrain difficult to conquer.

The numerically superior Italian army was led by Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna, a proponent of the frontal assault, who had planned to break into the Slovenian plateau, take Ljubljana and then threaten Vienna.

On the side of numerically weaker Austro-Hungarian army was Field Marshal Svetozar Boroević, a Serbian Croat and the only non-Austrian commander of this rank, who managed to persuade Emperor Franz Joseph that what was believed to be an indefensible part of Slovenia was is in fact worth defending, which placed him in command of Soča.

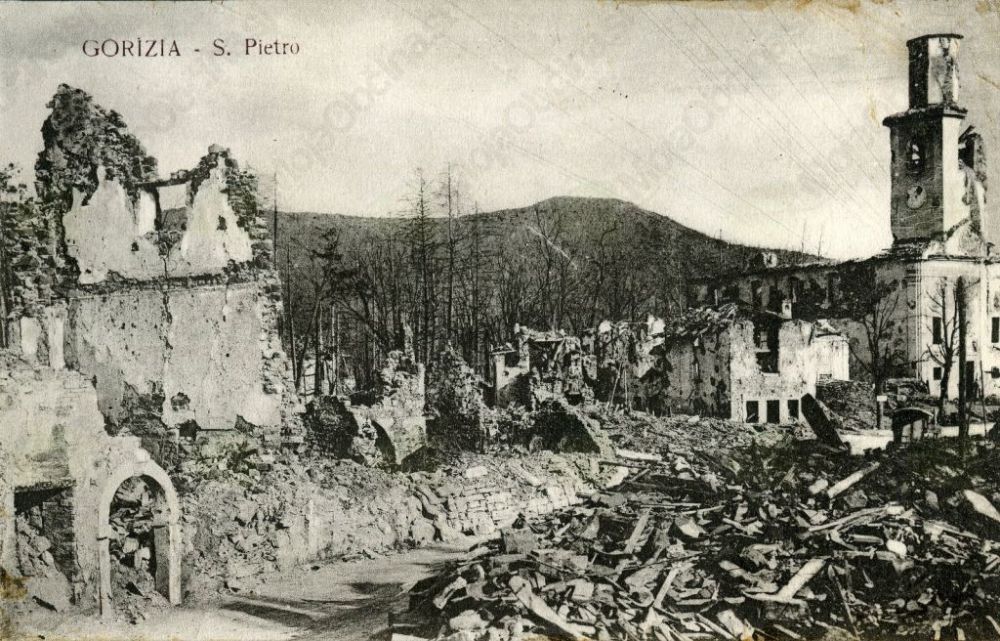

The terrain did in fact prove difficult for the Italian offensive, and the battle line practically didn’t move for the first eleven battles that took place over the following two years, exerting tremendous suffering not only on the troops but also the local population, who found themselves in the middle of the crossfire, famine and disease.

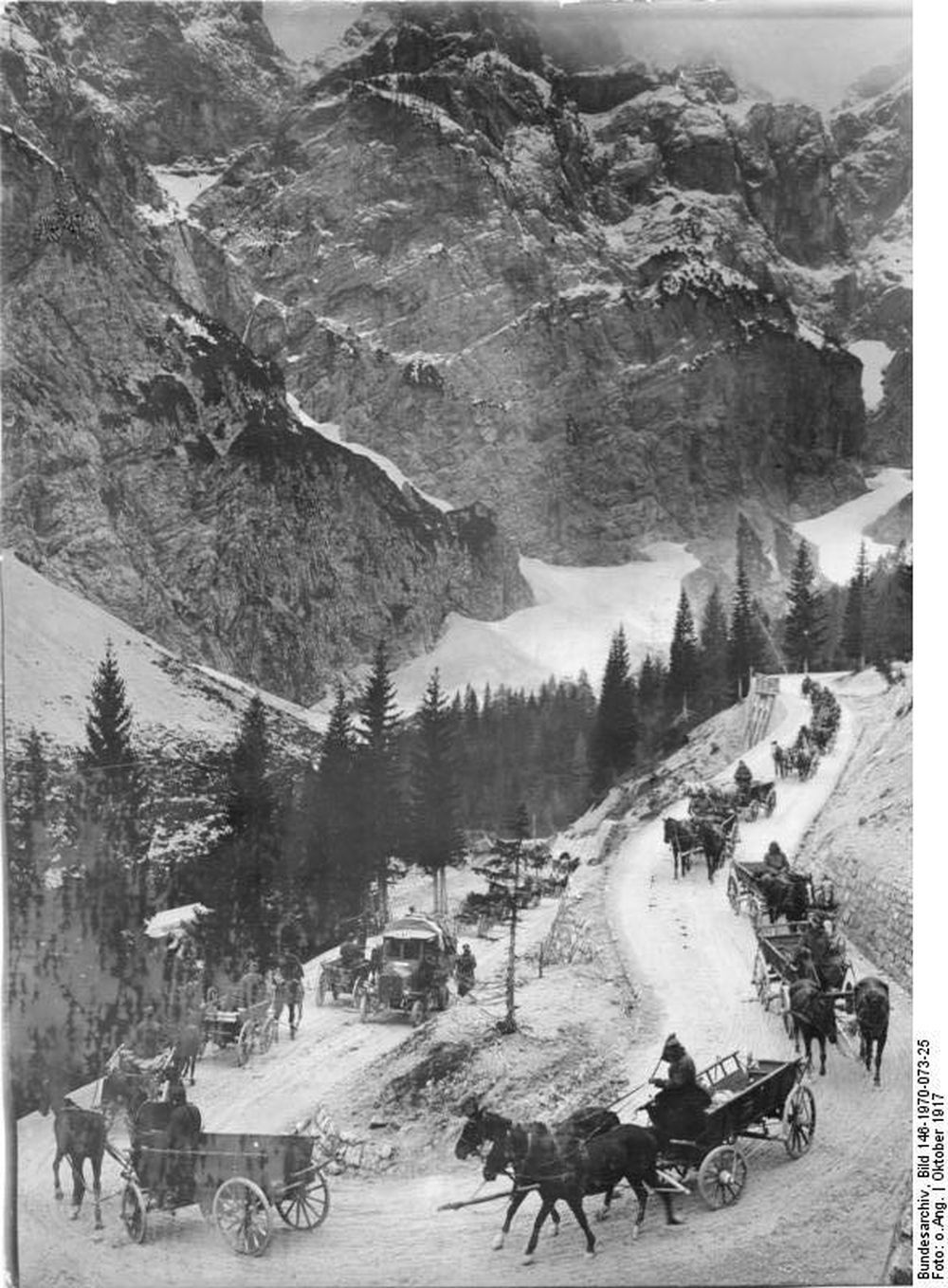

In the second half of 1917 the Austrian-Hungarian army was not only exhausted by years of war in steep mountain trenches, but also losing morale due to lack of progress and the aspirations for independence by various peoples under imperial rule. Emperor Karl I (Charles I), Franz Joseph’s successor and the Austrian commanding officer, decided to ask the Germans for help. If the Soča Front had fallen, the Austrian army would have collapsed and German offensive in the western front might fail as well. The Germans agreed and in September 1917 the plan for attack was drawn which was supposed to happen on October 22, but the date eventually changed to the 24th due to preparation delays.

Italian commanders began suspecting that Austria was preparing an offensive on September 14th, when it the closed border with Switzerland to prevent information from being leaked. By the end of the month the Italian command headquarters were informed about the presence of the German officers in the Tolmin area and Grahovo by Bača, and then about the arrival of Germans to Ljubljana and Tolmin at the beginning of October.

Despite all the warnings that an attack would occur somewhere in the upper Soča valley, the Italian commander Cardona believed that the Austrian offensive would occur at Banjšice plato near Gorica, so he moved most of the artillery units there.

The traditional military wisdom, which Cordona had followed, dictated the preferential capture of the hills from where the surroundings could be controlled. The German and Austrian strategists turned the idea upside down, planning to attack through the valley where the enemy was most vulnerable, in order to surround the heavily fortified hills and take them down one by one in the second phase of the offensive. In realization of this plan, they got a lot of help from the weather, as on the day of the attack it rained in the valley and snowed in the mountains.

Generally speaking, the 12th battle of Soča, also known as the Battle of Kobarid or the Battle of Caporetto, is considered the first to successfully employing the vague strategy of blitzkrieg commonly believed to be a WWII invention: infantry break through the weakest link in the adversary’s defense line, getting through behind its back and finishing it with artillery after it tries to follow.

Italian defense lines were well-fortified and equipped. In fact, the positions were carved into stone walls, making them accessible from the front face only. To get to their positions, which were distributed in three parallel defense lines, one would also have to get over the wire hurdles first.

The Austro-Hungarian and German army decided to solve the problem by the use of gas, which had already been used by the Austrian army in 1916. The gas used then was chlorine. This time, two gasses were prepared to deploy, chloroarsine and phosgene, the first one being a sneezing agent which seeped through the gas mask filters and caused an irritation which would force soldiers to take their masks off and thus inhale the second gas, phosgene, the deadly poison.

The battle began at two in the morning, when more than 111,000 gas grenades, the first the ones marked with blue crosses, then the ones with green crosses, were shot at the Italian side. Then the front was quiet till six in the morning, when full fire opened at the attempts to fill in the gaps in the defense lines. The infantry then moved through the valley with almost no resistance, advancing about 25 kilometers towards Italy on the first day alone.

Eventually the attackers were stopped at the Piava River, where they were decisively defeated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October 1918.

Austria-Hungary surrendered on 11 November 1918. The larger part of Carniola joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Kingdom of Yugoslavia), while Italy got its promised spoils of war (apart from Dalmatia) that included the former Austrian littoral with the border line drawn just under the peak of Triglav.