“A fire burned inside me and I knew only two ways out: either to keep stoking it or allow myself to be burned by it.” Nejc Zaplotink, Pot

There are many moments of horror when reading Bernadette McDonald’s Alpine Warriors (2015). The horror of snow, ice and wind to contend with, along with vertical walls, overhangs, collapsing seracs, avalanches, frostbite, lost shoes, exploding stoves, and death. And there is, as in every climbing book, death aplenty, the narrative always taking an ominous turn when recollections slip away and it becomes clear the climber in question never got to tell his side of the story from this point on, that they disappeared into the snow.

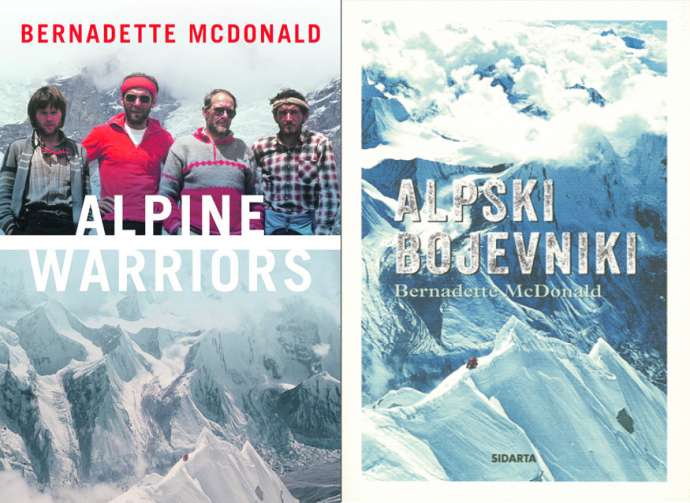

Alpine Warriors, a follow-up to McDonald’s 2008 book on Tomaž Humar, tells the story of two or three generations of Slovenian climbers who came to prominence in the 1960s to 1990s. This small group made many first ascents and established new routes up the most difficult faces. They were also key players in the dramatic changes overtaking the sport of alpinism as it evolved from a nationalist, state-sponsored activity to a more individual and commercialised one, with documentaries, energy bars and branded jackets, not to mention the opening of Everest to weekend climbers and those in mid-life crises. The same years saw a move from huge, months-long siege-style expedition climbs with dozens of high altitude porters and tons of equipment, to the light and fast style that at its most extreme ends up in solo ascents with only what you can carry in a backpack, up and down mountain in a few days.

The latter, exemplified in the book by the likes of Tomo Česen (b. 1959, Kranj) and Tomaž Humar (b. 1969 Ljubljana, d. 2009 Nepal), may seem more dangerous to non-climbing readers, but there’s a logic to it. The faster you move, the less danger you’re exposed to in terms of the elements. Think of camping out on the face of a mountain as like playing Russian roulette, and each day, as the sun warms the face, there are avalanches, sometimes lasting for hours, meaning in some places there’s only four hours of safe climbing, during which you need to make some ground and then dig a snow cave before the weather turns. The book is thus full of extreme events, amazing escapes and tales of endurance that appear superhuman. And despite all the skills of the climbers, and all their good judgement and experience, sometimes people just vanish, overwhelmed by the forces of nature, and other times they make it down, frostbitten and exhausted, having survived through the luck of the draw.

Manaslu - Konec poti Nejca Zaplotnika from Anže Čokl on Vimeo.

McDonald picks Nejc Zaplotnik (b. 1952 Kranj, d. 1983 Nepal) as the thread that runs through this group of climbers, who either knew the man or grew up hearing about him, not least through his book Pot. Despite its lasting success in Slovenia this work remains untranslated, but the title means “the Path” or, in a more Daoist sense, “the Way”, and the excerpts in Alpine Warriors set out a philosophy of climbing and being in the mountains that’s very tempting if divorced from the realities of life at 8,000 metres – “A path leads nowhere but on to the next path. And that one takes you to the next crossroads. Without end.”

The story begins in 1960, with the first Yugoslav team being sent to the Himalayas as part of a state-funded expedition, with the bulk of the talent coming from Slovenia. As McDonald notes, “the topography, combined with the hard-working, pious, matter-of-fact Slovenian temperament, honed and perfected under German/Austrian domination, created the perfect climbing machines.”

One side the of the narrative thus follows the changes in Slovenian society from the simplicity and relative poverty of the 1960s and 70s, when just leaving the country with visas and enough equipment was a trial, to the more open and individualistic 80s, 90s and beyond, when media interest and commercial sponsorship gave climbers more options than following the dictates of the Alpine Association. As McDonald tells it, the Association, as a nationalist endeavour, remained focused on goals such as climbing all 14 eight-thousanders, while the climbers themselves often had their own ambitions, like finding new routes up challenging faces, no matter what the height or where their partners came from (with, for example, Marko Prezelj forging a long partnership with the American Steve House - as seen in the following documentary, along with Vince Anderson).

Within this setting McDonald sets up various the personality conflicts, making clear there’s not one type of climber, even at the highest levels. Zaplotnik is thus presented as the romantic mystic, Silvo Karo (b. 1960 Ljubljana) and Marko Prezelj (b. 1965 Kamnik) as taciturn and plain-spoken (the latter on Kangchenjunga “At first it looks shit, and then you begin to solve the problems. Without complexity I am not challenged.”) and Tomaž Humar as an unstable, driven man, pushing himself into a public role and then retreating from it, eventually dying alone at the top of a mountain after his life at base level seemed to have fallen apart.

There are many scenes when even the most imaginative reader will struggle to feel what it’s like to experience 200 km per hour gusts of wind or -36°C while trying to bivouac on a ledge “three butt cheeks wide”, or to find your tent has been crushed by snow, equipment lost, ice axe shattered, partner vanished, with no hope of rescue but a will to live and endure that might not be enough. These are extraordinary men (and a few women), the kind who can say, like Tomo Česen,“I knew…that I could go three to four days without food and two or more days without sleep”.

Česen himself is presented as a pivotal figure, both for his early acceptance of sponsorship as a way of breaking free of the Alpine Association, and for the scandals related to claimed ascents of Jannu and Lhotse’s South Face, which suggest how commercial pressures changed the nature of the sport, demanding ever-greater spectacles, leading to the circus that often surrounded McDonald’s last focal climber, Tomaž Humar.

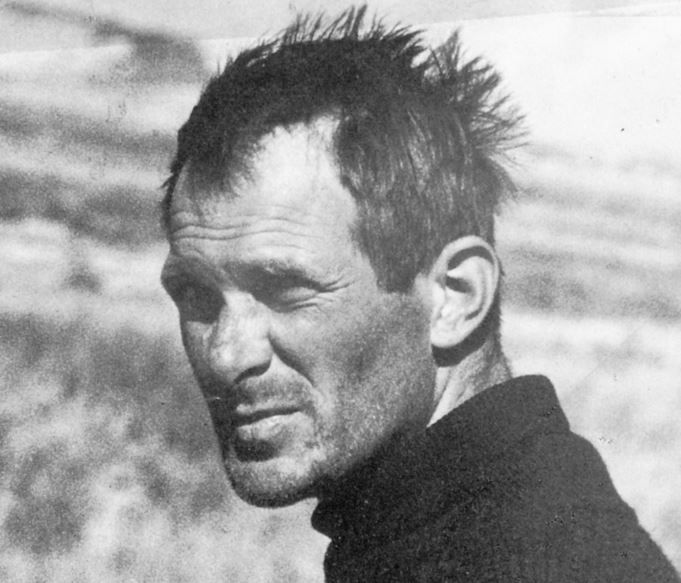

Others covered in the book include Tone Škarja (b. 1937 Lubljana), Stane Belak-Šrauf (b. 1940 Ljubljana, d. 1995 Mojstrovka, avalanche), Marjan Manfreda (b. 1950 Bohinjska bela, d. 2015 Gorenjska, traffic accident), Stipe Božič (b. 1951 Croatia), Drago Bregar (b. 1952 Višnja Gora, d. 1977 Pakistan), Viki Grošelj (b. 1952 Ljubljana), Borut Bergant (b. 1954 Podljubelj, d. 1985 Nepal), Franček Knez (b. 1955 Celje, d. 2017 while climbing in Slovenia), Andrej Štremfelj (b. 1956 Kranj), Slavko Svetičič (b. 1958 Šebrelje, d. 1995 Pakistan) Janez Jeglič (b. 1961 Tuhinjska dolina, d. 1997 Nepal), and Vanja Furlan (b. 1966 Novo mesto, d. 1996 Mojstrovka). There are thus too many interesting characters here for this review to touch them all, but one we’ll highlight is Aleš Kunaver (b. 1935 Ljubljana, d. 1984 Jesenice, helicopter accident), the team leader on many expeditions who was able to bring out the best in his climbers while remaining in the shadows and often off the summit. It was also Kunaver who opened the first school for Sherpas in 1979, in order to reduce accidents in the Himalayas, and from whom we get the quote “In the mountains magnificence is diametrically opposed to comfort”.

Aleš Kunaver. Source:

And while there are deaths throughout the book many of the characters are still alive and active on the scene, firmly enmeshed in the both the history and present of alpinism and climbing in general, not just in a Slovenian context, but globally. The move from high to steep mountains, to walls with more technical difficulty than altitude, can be seen in pop culture triumphs like Alex Honnold’s free solo of El Capitan, as well as less publicised ascents such as that of the North Face of Latok, the “holy grail” of high altitude climbing that was finally achieved in summer 2018 by a Slovene-British expedition consisting of Aleš Česen (Tomo’s son), Luka Stražar and Tom Livingston (as reported here).

So although the book Alpine Warriors was published in 2015, and ends with Humar’s death, the story continues, and is one that those of us who live in Slovenia can easily feel a personal connection to, through the men and women who live among us when not climbing, and through the stunning landscape that has shaped such people and inspired dreams of the freedom that’s possible when one leaves the towns and cities and goes up into the mountains with good friends or alone.

In short, I enjoyed this book a lot, and if any of the above struck your interest then consider picking up a copy of Alpine Warriors, by Bernadette McDonald, and learning much more about Slovenia’s climbers. I’ve seen both English and Slovene editions in bookstores here, and it can also be ordered online in paper or ebook versions.