Ljubljana related

STA, 27 April 2020 - Resistance Day (aka Day of Uprising Against Occupation, dan upora proti okupatorju) will be marked in Slovenia today to remember the establishment of the Liberation Front, an organisation that spearheaded the resistance movement against the occupying forces during World War II.

Given the coronavirus lockdown, there will be no national ceremony marking the public holiday and the 79th anniversary of the Liberation Front.

However, President Borut Pahor and the head of the WWII Veterans' Association, Marijan Križman, will address citizens from the Presidential Palace in the morning.

They will also lay a wreath at the Liberation Front monument in Rožna Dolina borough in Ljubljana, in front of the house in which the organisation was formed.

National Assembly Speaker Igor Zorčič will lay a wreath at the tomb of national heroes in the park near the Parliament House.

Since the Presidential Palace will not be open to the public, people will have the opportunity of visiting the president's chambers online.

For Slovenians, World War II started on 6 April 1941, when Germany attacked Yugoslavia.

The Anti-Imperialist Front, as the Liberation Front was initially known, was formed 20 days later, on 26 April 1941, the day when Hitler visited the city of Maribor.

The fact that its establishment is marked on 27 April is due to a minor historical error.

In 1572 one of the most important advanced peasant revolts occurred in the lands of today’s Slovenia and Croatia. Most probably it began on today’s date, April 24.

Peasant rebellions, which spanned over a period of 250 years in Slovenia, had five notable events, starting with the Rebellion of Carinthia in 1478 and concluding with the 1713 Rebellion of Tolmin.

Among the main causes of peasant revolts were the reintroduction of duty in kind, increase in feudal tax and serjeanty, violence against serfs by feudal lords, Turkish incursions and wars, on top of agricultural disease and weather-related disasters.

For these reasons serfs began organizing themselves into farmers’ associations, or “punti” as they were called in Slovenian. Between the 15th and 17th centuries “punti” were targeting feudal lords, while at the beginning of the 18th century they were directed against the state institutions and Emperor.

The biggest rebellion in Slovenia occurred in 1515 with about 80,000 participants, most probably depicted by Albrecht Dürer in his 1515 sketch for the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.

However, one of the most important peasant revolts occurred in 1572 adn 1573 across today’s Slovenia and Croatia, and was particularly advanced in terms of organization and political program of the peasants.

The rebels’ political agenda was to replace the nobility with peasant officials who were directly responsible to the Emperor, and to eliminate all feudal possessions of and obligations to the Roman Catholic Church. The peasant government was composed of the main leader Matija Gubec, (Cro: Gubac), and Ivan Pasanec and Ivan Mogaić as its main members. Their plans also included the removal of provincial borders, the opening of freeways for trade and self-management by farmers.

Although historians mainly agree that the main cause behind the Slovene-Croatian rebellion was economic in nature, the rebellion is often associated with Baron Ferenc Tahy and his cruel treatment of the serfs. In 1567 the Imperial commission agreed to investigate Tahy’s competence in run the estates by hearing 508 testimonies against him. Unfortunately, no measures other than the writing of the minutes of the hearings were taken – although these ran for at least six metres – which is why Tahy and his misrule remain the main reason for the rebellion in popular belief.

The rebellion started in 1572 and was initially limited to three Tahy estates. Eventually the revolt spilt over across Croatian Zagorje, lower Styria and parts of Lower and Upper Carniola, with an estimated 12,000 rebels, some 4,000 of whom were killed in clashes with feudal armies.

The rebellion concluded on February 9th, 1573 with the capitulation of the serf army and the following punishments of the leaders: Matija Gubec was crowned with a red-hot heated iron crown and quartered, while the other leaders were decapitated.

A feature film directed by Vatroslav Mimica was made about the events in 1975. The movie is spoken in the dialect of Zagorje, which sounds like a mixture of Slovenian and Croatian or perhaps the proto-language of the two. The film is also available on YouTube:

STA, 6 April 2020 - Slovenia is marking this week 30 years since holding its first free multi-party elections. The winning coalition of parties that formed an opposition to the Communist Party and its affiliates, would lead the country to independence a year later. Speaking today, two officials elected at the time say the country has not realised its full potential.

The late 1980s Slovenia, then still part of Yugoslavia, saw a buzz of burgeoning efforts by scholars, authors, cultural workers and some politicians pushing for the country to introduce a pluralist democratic system and market economy and to break away from the socialist federation.

Gathering momentum through a series of landmark events such as the publication of a manifesto for Slovenia's independence in the 57th volume of the literary journal Nova Revija, the JBTZ trial and the mass protests it triggered, the May Declaration calling for independence and the Slovenian delegation's walking out of the Communists of League of Yugoslavia, the campaign led to the first multi-party election on 8 April 1990.

On that day voters picked two-thirds of the delegates to the 240-member tricameral Assembly; 80 delegates to the socio-political chamber as the most important house, and 80 delegates to the chamber of local communities, with the election to the chamber of "associated labour" following on 12 April.

Of the 83.5% of the eligible voters who turned out, 54.8% voted for DEMOS, the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia, who brought together the parties that had been founded in the year and a half before as part of the democratic movement that demanded an end to the one-party Communist regime. DEMOS formed a government which was appointed on 16 April with Lojze Peterle as prime minister.

The winner among individual parties was the League of Communists of Slovenia - Party of Democratic Renewal (ZKS-SDP), the precursor to today's Social Democrats (SD). The party won 14 seats in the socio-political chamber, which would evolve into today's lower chamber, the National Assembly.

However, with the exception of the chamber of associate labour, DEMOS won a convincing victory in the then Assembly, winning 47 out of the 80 seats in the socio-political chamber, of which 11 were secured by the Slovenian Christian Democrats (SKD).

Along with parliamentary elections, Slovenians also cast their vote for the chairman and four members of the collective presidency. Milan Kučan, the erstwhile Communist leader, was elected chairman after defeating DEMOS leader Jože Pučnik in the run-off on 22 April with 58.59% of the vote. Matjaž Kmecl, Ciril Zlobec, Dušan Plut and Ivan Oman were elected members of the presidency.

Looking back, Plut says the time of Slovenia's first democratic election marked two sets of political change; the political system's change to democracy and the country's becoming independent. The party that would not support those two key goals had little chance of wining voters' trust, he has told the STA.

Plut led the Slovenian Greens, the party that won 8.8% of the vote in the 1990 election, which he says was the highest share of the vote among all green parties in Europe. He believes the reason the Greens would not repeat the feat again was that the right-wing faction prevailed following the party's joining DEMOS, which meant a party naturally favoured by left-leaning voters lost its voter base.

Asked whether the situation would be different today had Pučnik won the presidential run-off, Plut does not think it likely: "The voters had obviously made a well thought-through decision for a balance. DEMOS won the assembly, while Kučan was elected presidency chairman. The latter had a host of political experience, which came very handy at the time."

"Could anything be different? I don't know. We can only guess," Kmecl says when offered the same question. Kmecl, a Slovenian language scholar, literary historian and author, remembers the time of the first democratic election as euphoric, "however, it hasn't brought what we all thought it would".

Above all, he had expected more solidarity. "Instead, it all ended in terrible egotism. I have always argued that neo-liberalism is harmful for small entities such as the Slovenian nation because it works only by the logic of quantity and power."

Plut agrees that not everything went the way it should have following independence. Most of all, he believes that Slovenia has failed to capitalise on its position as the most successful of all post-social countries in terms of economic indicators at the time.

"The entire politics, DEMOS included, soon forgot the key motive behind independence - increasing the prosperity of Slovenia's citizens. Hence the rapid increase in social and regional differences. There's no coincidence that public opinion polls show Slovenia hasn't realised the potential of independence," says Plut.

"In politics in general, the interests of individual political parties have too often been more important than people's prosperity. There's a lack of awareness that it is the politicians who are responsible for people's prosperity," says Plut.

All our stories tagged Slovenian history are here

Vinko Bogataj is a former Slovenian ski jumper, born on today's date, 4 March, in 1948.

In 1970 Bogataj experienced a nasty crash at Oberstdorf flying hill in Germany, derailing at the take off ramp and flying down to the ground, missing most of the by-standing spectators and spruce stumps. He got away with a concussion and a broken ankle, and was back to the hills in the following season.

The crash did not make much of an impression in a European ski jumping context, and without much noise Bogataj eventually retired from ski jumping, switching to painting instead.

However, American ABC’s Wide World of Sports crew who was also present at the 1970 Oberstdorf event, made sure Bogataj’s crash wouldn’t go unnoticed. The footage soon found way into the title sequence of the programme, providing the “agony of defeat” part of the visuals in support of the opening statement: “Spanning the globe to bring you the constant variety of sport…the thrill of victory…and the agony of defeat…the human drama of athletic competition…This is ABC's Wide World of Sports!"

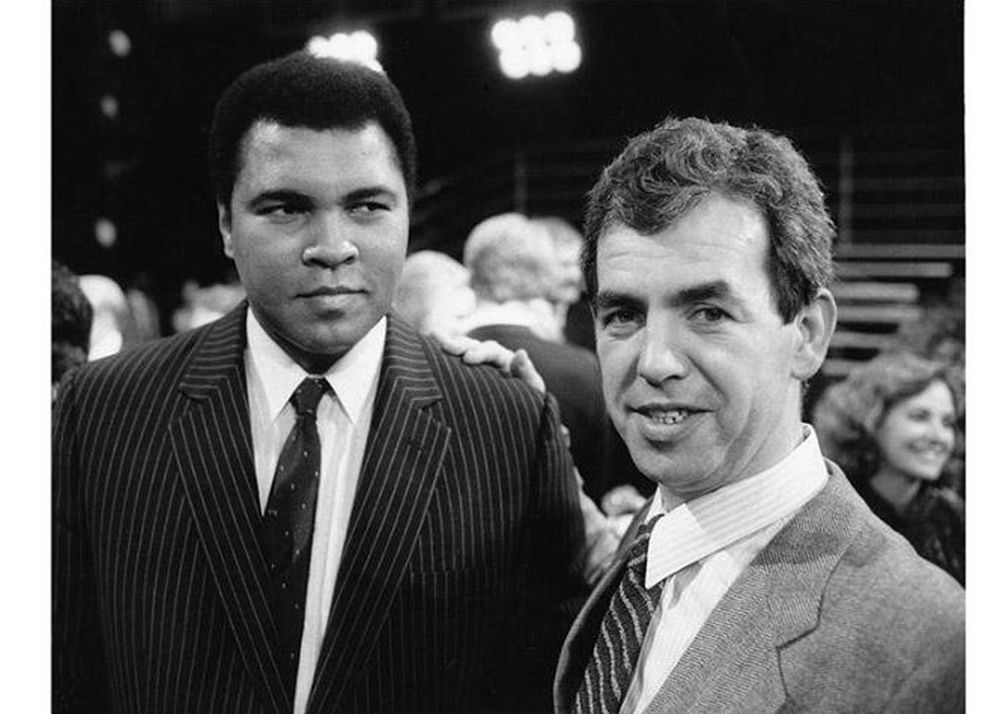

In 1981 Wide World of Sports celebrated its 20th anniversary in New York and Vinko Bogataj was invited to attend. It was only at this ceremony that he realised that he must have become quite famous in the USA. Especially by the end of the ceremony, when Muhammed Ali approached to get his autograph.

In 1997, Wide World Classics filmed another report on Bogataj, looking back at his role in the show.

The last appearance of Vinko Bogataj in the American media occurred in 2016, when ESPN published an interview with him, his daughter in the role of translator.

In contrast to Bogataj’s ski jumping fame in the USA, he’s now better known locally as an artist. Just a few months following his ESPN interview, Bled Castle, showcasing Bogataj’s art exhibition, wrote: “Did you know that besides his big love for painting Vinko Bogataj also used to be a member of the Yugoslav ski jumping team in his youth?... Welcome to the Tower Gallery. The exhibition of Vinko Bogataj’s paintings is open until the end of the month every day during the opening hours of Bled Castle.”

photo: Bled Castle, Facebook

In 1987 workers in the state owned company Litostroj, a Ljubljana-based heavy machinery manufacturer, began their strike, which many consider one of the crucial events in the democratisation of Slovenia.

The strike of about five thousand Litostroj workers under the leadership of an engineer France Tomšič lasted between December 9 and 15, expressed no confidence into the existing one-party governing rule by demanding that unions be able to become independent, and countered the ruling party at the political level by establishing an initiative committee of the Social Democratic Union of Slovenia.

Since the existence of another party, besides the ruling one, was not constitutionally possible at the time, the Social Democratic Union’s constitutional meeting could only occur on February 16, 1989, after the constitution had been changed.

The new party’s first leader was Tomšič, and Jože Pučnik became his successor in November 1989. At the 1993 congress, Janez Janša – current leader of the SDS – was elected as the party’s new leader.

In 1989 DEMOS, or the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia (Demokratična opozicija Slovenije), was established, a coalition of democratically elected parties, which won the first democratic elections since 1945 and carried out the Slovenian independence project.

In 1980 the dictator of the Socialist Yugoslav federation Josip Broz-Tito died, and the economic, nationalistic and political tensions in the country started to grow.

In the Socialist Republic of Slovenia the first political party, Slovenian Farmers’ Association (Slovenska kmčka zveza), was established in 1988, and several more followed in 1989, as part of the democratic movement challenging the one-party political system.

Slovenian National Assembly passed several constitutional amendments in September 1989, which among other freedoms granted the rights of national self-determination and democratisation of Slovenian political system. In December the Assembly then first passed a law on political associations, setting the legal grounds for establishment of political parties (before this they had to be registered as associations or societies) and then called the parliamentary elections for April 8, 1990.

Several of the newly established parties, including the Slovenian Farmer’s Association, Slovenian Democratic Union, Slovenian Social Democratic Union and the Slovenian Christian Democrats signed a cooperation agreement, forming the DEMOS coalition, which won with 54.8 % of the vote in 1990, beating the parties which emerged from the crumbling Communist Party organisations.

DEMOS then formed the first democratically elected Slovenian government since 1945, which successfully carried out the referendum on independence on December 23, 1990, when 88.2% of all voters favoured Slovenia breaking away from Yugoslavia, and then June 25, 1991, the National Assembly on passed the declaration of independence.

The DEMOS government fell in 1992 due to disagreements with regard to changes in economic system, most notably, the question of how the privatisation of public companies should take place, a question then addressed by the second democratically elected government of Janez Drnovšek.

STA, 23 November 2019 - Slovenia observes Rudolf Maister Day on Saturday, remembering the general who established the first Slovenian army in modern history and secured what later became Slovenia's northern border. The holiday commemorates the day in 1918 when Maister (1874-1934) took control of Maribor.

Several events commemorating Maister were held this week. The main ceremony, on the eve of the holiday in Murska Sobota, was addressed by parliamentary Speaker Dejan Židan.

Židan praised Maister's courage, patriotism and determination also in his address to MPs yesterday. He said that Rudolf Maister Day was a great opportunity "for us to ask ourselves how do we contribute to a better society on a daily basis and whether we are worthy of the great deeds of our ancestors".

He added that Maister and his fighters could serve as an inspiration particularly to "us, current decision-makers" to be "bold enough to join forces in our efforts for a better future".

Interior Minister Boštjan Poklukar noted in his message marking the holiday that Maister had not hesitated for a minute before taking his army into battle for "our northern border".

After laying a wreath at the monument to Maister in front of the Defence Ministry building on Friday, Defence Minister Karl Erjavec said Maister, a superb army commander, had felt at the end of the First World War that a historic moment is coming.

"It was a time, when we were able to take advantage of the first opportunity to get to independent Slovenia. It was a dream of many generations, many have given their lives for this goal. This is why is consider General Maister's actions as the first step towards our country," he stressed.

Today, President Borut Pahor will welcome visitors at the Presidential Palace, and the honorary guard of the Slovenian Armed Forces will be lined up in front of the building.

In Maribor and Kamnik, where Maister was born, memorial plaques will be unveiled, honouring the ardent Slovenian patriot.

Following the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Major Maister prevented Maribor and the Podravje area from being made part of German Austria, the country created after WWI comprising areas of the former empire with a predominantly German-speaking population.

On 30 October 1918, the German city council declared Maribor and its surroundings part of German Austria, which Maister found unacceptable.

He set up a Slovenian army of 4,000 soldiers, disarmed the German Schutzwehr security service, and disbanded the militia of the German city council.

The general then occupied Slovenian ethnic territory, establishing the northern border between Austria and Yugoslavia that was later ratified by the Saint Germain Peace Treaty. The same border still runs between Slovenia and Austria today.

Maister is buried at Maribor's Pobrežje Cemetery, where he has a modest grave.

23 November has been observed as a public holiday since 2005, although not as a bank holiday.

All our stories on Slovenian history are here

In 1948 the first Slovenian feature film with sound, titled On Our Own Land (Na svoji zemlji), was released in Union Cinema (Kino Union) in Ljubljana. The film, directed by France Štiglic, was nominated for a Palme d’Or at the 1949 Cannes Film Festival.

The first film ever made in today’s Slovenia was a two-minute long portrait of Ljubljana, filmed from Ljubljana Castle in autumn 1898. The film, which has unfortunately been lost, was then shown in Tivoli Park for about a week in May, 1899.

In 1905 three short films were made about the life in Ljutomer and in 1909 Ljubljana, a seven-minute film depicting Slavec Worker’s Choir’s 25th anniversary celebrations was created and can still be seen today.

In the years 1931 and 1932 two feature silent films celebrating mountaineering were made, that is In the Kingdom of the Goldhorn (V kraljestvu Zlatoroga), which is also the first Slovenian feature film, and The Slopes of Mount Triglav (Triglavske strmine).

After these nothing else was filmed for about a decade, as if the only thing Slovenians needed at the time was to put Triglav on film.

In 1941, just before WWII reached Slovenia, O Vrba was made, a documentary film that shows the house of the Slovenian poet France Prešeren when it was opened as a museum, an event that happened on the same day the film’s creators found out about the German invasion of Poland. The film’s release, however, had to wait until 1945, due to cultural silence imposed by the occupying forces during the war.

Another film was also released in 1945, the first post-war film and documentary with some acted scenes inserted, titled Ljubljana Welcomes Liberators (Ljubljana pozdravlja osvoboditelje).

In 1948, however, Slovenia finally got its first proper feature movie with sound. On One’s Own’s Land was based on the novel Grandpa Orel (Očka Orel) by Ciril Kosmač, and depicts partisan resistance during the last two years of WWII in the Slovenian Littoral, occupied by the Italians, then after capitulation of Italy when it was occupied by the Germans.

The film was the first produced by the company Triglav Film, established in 1946.

You can watch it below, although it’s only available online with Croatian subtitles.

In 1896 a four-kilometre long electric grid with 700 light bulbs came into operation in Kočevje, the event marking the beginning of the public distribution and supply of electricity in Slovenia.

The historical use of electricity in Slovenia begins in Maribor, where the first electric light illuminated the steam mill in 1883. The beginning of electrification, however, is considered the year 1894, when the first public hydroelectric plant began operating on Sora River in Škofja Loka.

The main purpose of the hydroelectric plant in Škofja Loka, however, was not to provide electricity for public use but rather for the needs of a thread factory, which was also the producer of the energy it needed. The surplus of electricity was sold to the city government and could support about 40 electric bulbs.

The hydro power plant in Kočevje, which was established to deliver water and electricity to the citizens, beginning on today’s date in 1896, is therefore considered as the beginning of electrification of today’s Slovenia.

In comparison, in Ljubljana the first electric bulb did not get turned on until January 1, 1898.

In 1918, following the end of WWI, the Serbian army officer Stevan Šabić and some of the Serbian army troops that have been captured by Austro-Hungarians during the war made a stop in Ljubljana on their way to Serbia and prevented its plunder by retreating military gangs and its planned occupation by the advancing Italian forces. Lieutenant Colonel Švabić, having the highest rank in the land he found himself in, also prevented the capture and plunder of Trbovlje and some other Slovenian towns.

In the chaos that followed the end of the WWI the newly established State of Serbs Croats and Slovenes (a month later the state embraced the Serbian king becoming a Kingdom itself) was not yet recognised and did not have its own army presence in all of the territories it claimed, especially in Slovenia, which used to be part of the now defeated Austrian Empire. With no troops present, the land was open for post-war looting, violence and changing of geopolitical circumstances which could potentially affect the new border agreements which were soon to follow.

Post-war Hungarian military violence against the Slovenian majority population in Prekmurje ended with the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, where Hungary was forced to sign the Treaty of Trianon, which granted people the right to self-determination and allowed Prekmurje to join the Kingdom of SCS.

In Maribor, where on October 30, 1918 the German city council declared lower Styria (Štajerska) as part of the Austrian territory, General Rudolf Maister, who managed to mobilise 3,000 troops, disarmed the German guard on November 23, then continued a military campaign for Slovenian Styria and Carinthia.

On the Western border, however, things were a bit more complicated. The “people’s self-determination” principle that guided the Treaty of Trianon of the Paris Peace Conference was forgotten here in favour of the secret 1915 Treaty of London, which promised Italy large territorial gains in case of the Entente Powers’ victory. The controversial treaty became public after Lenin publicly denounced it in 1917.

Nevertheless, about 1/3 of the lands where Slovenians lived went to Italy, including the entire Southern and Northern littoral right up to the peak of Triglav. And in the post-war chaos with the central part of the country undefended, Italians turned their eyes on the capital, Ljubljana, as well.

On November 6, 1918, a Lieutenant Colonel of the Serbian army, Stevan Švabić, and other Serbian prisoners of war made a stop in Ljubljana after being released from Austrian war camps. According to Švabić’s account, Ljubljana train station was in a complete disorder: there was a train with 15 cars full of armed Hungarians on a nearby track and several other trains with armed militias present at the station. Immediately after his arrival at the station he was already being looked for by Adolf Ravnikar, sent to find help by the city authorities. Ravnikar explained the situation as alarming: out of control Austrian soldiers were returning from the front, while the Italian army followed them. If immediate help was not found, gangs would ransack the city and empty the military depots.

Understanding the urgency, Švabić gathered his troops to restore some basic order in the city, while prepared to address the problem of the advancing Italian army which had by November 10 already reached Logatec and was heading towards Vrhnika.

By November 14, Švabič had about 2,000 men and probably got a permission from Zagreb, to send the Italian commanding officer in Vrhnika an ultimatum not to continue the advance of the Italian troops further to Ljubljana, as he would have find “use of weapons on allied forces most regretful”.

The ultimatum, which was based on a pretext that the allied forces, the Serbs, had already taken control of the surrendered Austrian territories, stirred a lot of confusion on the Italian side, which must have concluded that perhaps the Serbian army had indeed managed to reach that far north at such a short notice. Furthermore, additional pressure on the Italians to retreat came from the French, who were called to do so by the Serbs.

In the days that followed, the Italian army retreated from Vrhnika while only six days after his ultimatum Stevan Švabić was called to Belgrade, probably due to a presumed violation of the chain of command by signing his name on the document which threatened an allied country with the use of weapons.

In 1930 Stevan Švabić was awarded a deserving citizen medal by the City of Ljubljana and two streets in Slovenia are named after him: Švabićeva ulica in Trnovo, Ljubljana and Švabićeva ulica in Vrhnika.